Digital accessibility has become a very important consideration for both private and public entities. This is not only because legislation has been put in place to regulate the development of technology per se [1], or because it has a direct financial benefit on businesses [2], but also because there is a moral obligation to build inclusive technology that could be easily accessed by everyone.

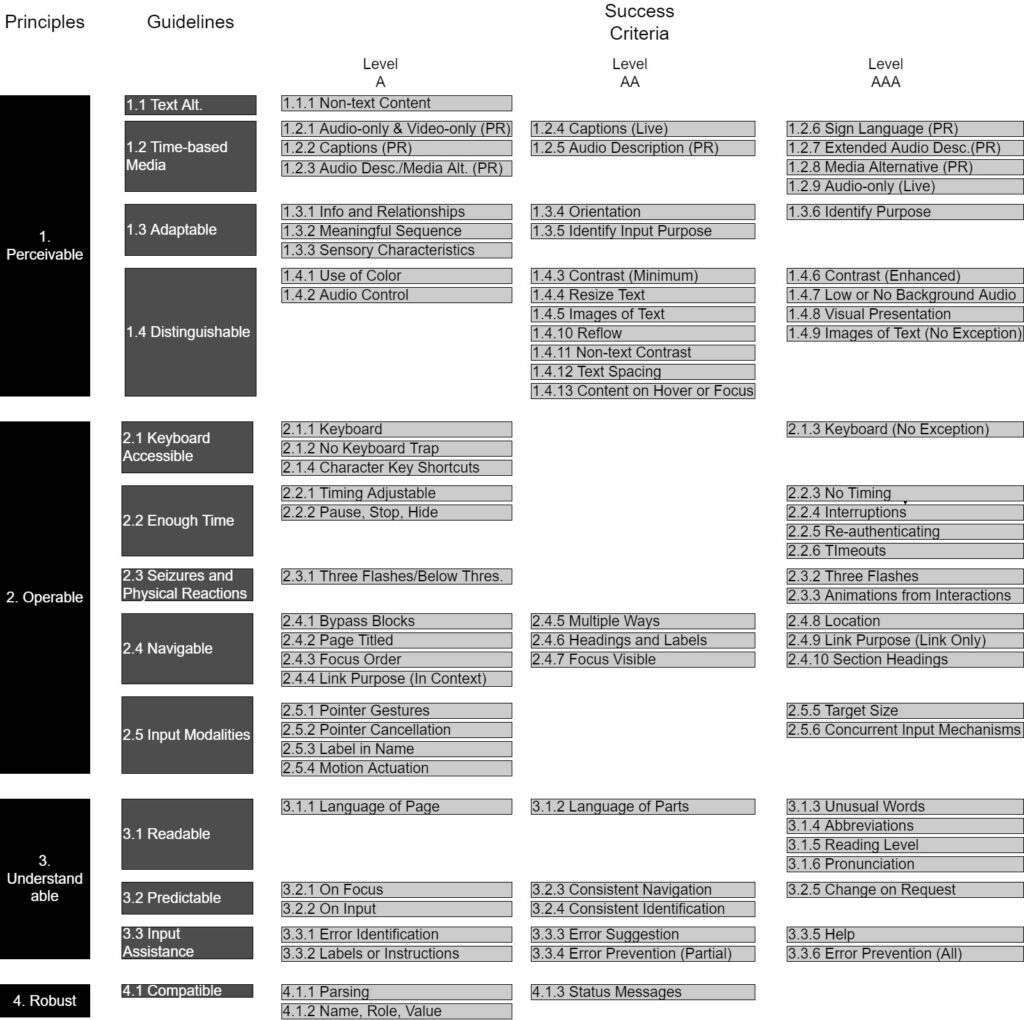

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) [3], which are the reference point for most laws and regulations pertaining to this area (such as the EU Web Accessibility Directive) consists of over 70 success criteria for web accessibility across three levels of conformance: level A, AA, or AAA. Digital products may conform to any of these levels, each requiring an additional level of effort with more rigorous tests. In previous studies on the subject [4] – [7], it was indicated that a higher level of conformance would result in higher levels of perceived usability.

For the purpose of this study, two functionally equivalent e-commerce websites were used in a controlled study. The first version did not adhere to any of the accessibility guidelines. On the other hand, the second version complied with WCAG 2.1 at level AA, which is the level of conformance typically recommended within national and international legislation, including the EU Web Accessibility Directive [8].

The study was split into three parts. The first part of the study set out to understand the participants’ familiarity with e-commerce websites. In the second part, participants were asked to perform a series of tasks on one of the websites (non-conformant or conformant). This study was conducted using a between-subjects approach. Therefore, participants were split into two groups, namely: a control group and an experimental group.

Participants in the control group were asked to carry out a series of tasks on a non-conformant version of the e-commerce site, while the experimental group was asked to carry out the same set of tasks on the version which conforms to WCAG 2.1 Level AA. Data points such as time-on-task and task completion rates were recorded, while participants were also asked to rate the perceived workload for each task using the Single Ease Question.

Finally, after completing all assigned tasks, participants were asked a series of questions regarding their experience, using standardised tools such as the system usability scale, along with a semi-structured interview aimed at shedding further light on their experience with the assigned site.

drowsiness detection process

References/Bibliography:

[1] W. (WAI), “Web Accessibility Laws & Policies”, Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.w3.org/WAI/policies/. [Accessed: 30- Jun- 2021].

[2] W. (WAI), “The Business Case for Digital Accessibility”, Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.w3.org/WAI/business-case/#accessibility-is-good-for-

business. [Accessed: June 2021].

[3] W. (WAI), WCAG 2 Overview. [online] Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI). Available at: <https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/> [Accessed June 2021].

[4] S. Schmutz, A. Sonderegger and J. Sauer, “Implementing Recommendations From Web Accessibility Guidelines: A Comparative Study of Nondisabled Users and Users With Visual Impairments”, Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, vol. 59, no. 6, pp. 956-972, 2017. Available: 10.1177/0018720817708397.

[5] S. Schmutz, A. Sonderegger and J. Sauer, “Implementing Recommendations From Web Accessibility Guidelines: Would They Also Provide Benefits to Nondisabled Users,” Human Factors The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 611-629, 2016.

[6] A. Aizpurua, S. Harper and M. Vigo, “Exploring the Relationship between Web Accessibility,” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, vol. 91, pp. 13-23, 2016.

[7] S. Schmutz, A. Sonderegger and J. Sauer, “Effects of Accessible Website Design on Nondisabled Users: Age and Device as,” Ergonomics, vol. 61, no. 5, pp. 697-709, 2017.

[8] W. (WAI), Web Accessibility Laws & Policies. [online] Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI). Available at: <https://www.w3.org/WAI/policies/> [Accessed June 2021].

Student: Eric Curmi

Course: B.Sc. IT (Hons.) Computing and Business

Supervisor: Dr Chris Porter