By understanding how students learn, PhD student MARIO MALLIA-MILANES and Research Support Officer STEPHEN BEZZINA are creating AI algorithms that can help teachers teach and learners learn.

Education is a vital element in a stable, just, and civilised society, yet the way we have been teaching and learning has not really changed much for hundreds of years. The reason for that is that human-to-human interaction remains the best way we have to learn new concepts, discuss ideas, and put theories to practise. Technology, however, continues to permeate the classroom, and AI, as both our interviewees show, is now set to help facilitate the process with which human beings exchange information.

“Researchers are constantly trying to find a way to solve both new and age-old educational problems using technology and new ideas,” Mario explains. “In fact, when I started my PhD, my tutor had a challenge for me: to figure out why only a small percentage of students who register for online classes finish the course, and to propose a solution to help reduce the trend.”

Dedicating the past six years of his research to answering this question, Mario discovered that many people who join online courses often lose interest because of the lack of interactivity, which in turn leads to boredom.

“Psychology is the main driving force behind people’s decision to drop out, so my next task was to work out how students could be kept happy and interested during their online lessons. The answer came in the form of agent assistant collaborative learning (AACL), which uses the premise of collaboration, something we humans, for the most part, enjoy.”

AACL, as Mario explains, sees AI becoming the student’s ‘teammate’, helping them with any problems that arise, making suggestions, and keeping them interacting during the lesson.

“As in any other relationship, trust plays a big part in the creation of a bond between the student and the AI algorithm, so I also worked on creating an algorithm that could explain itself as it goes along. This, in many ways, demystifies the technology.”

Such systems may seem alien to us indeed, but even as we speak, it is being used to create algorithms that offer personalised and adaptive learning alongside the traditional teacher-student dynamic.

“Each student is unique and has distinct needs in the classroom,” Stephen adds. “For that reason, teaching can’t be a one-size-fits-all affair. Nevertheless, the logistics and expense of having a teacher for every student would make it impossible to sustain, so how can we find a solution?”

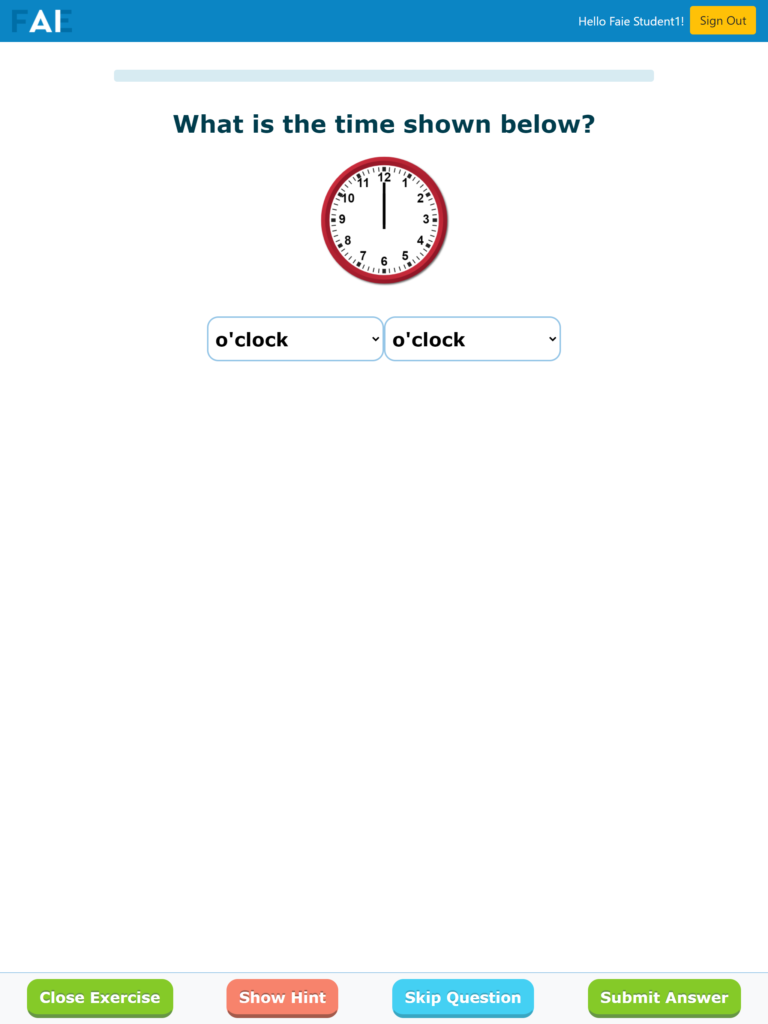

It is with this in mind that Stephen, as well as a number of other researchers, are currently designing and developing an AI system aimed at primary school mathematics students. This system, which can be operated from tablets and laptops directly in the classroom, is being programmed to offer students exercises and games based on the maths topic they would have covered that day, week, month, or academic year. The questions, however, would start off easy for all students and then, based on each student’s answers, the individual student’s system would decide whether to make the next question harder or to re-explain the subject through a video tutorial before giving them another shot at it.

“The system itself personalises learning and adapts to the child’s needs. Its function, however, isn’t to replace the teacher, but to aid in teaching both by giving the teacher more time to focus on students who are struggling, and through the report of each student’s work the system creates, which can help with the monitoring of progress.”

Stephen’s role in all this is that of gamification, which is the use of gaming elements in non-gaming contexts. This, in so many words, means that he has to figure out how to make the system fun for children to use by, for example, awarding badges at the end of the day, or creating different levels that may entice students to spend more time studying and learning.

In many ways, this also shows how, at a basic level, AI learning keeps things human: neither project is changing the way we learn or teach, and neither project is replacing the human-to-human interaction. Instead they are creating systems that aid educators and learners alike in order to develop a more symbiotic learning environment that makes the most of the abilities of the students.