For years, scientists have taught computers to understand sentiment in several global languages. Now, Master’s in AI student DAWSON CAMILLERI wants to use the work already there to boost our national language.

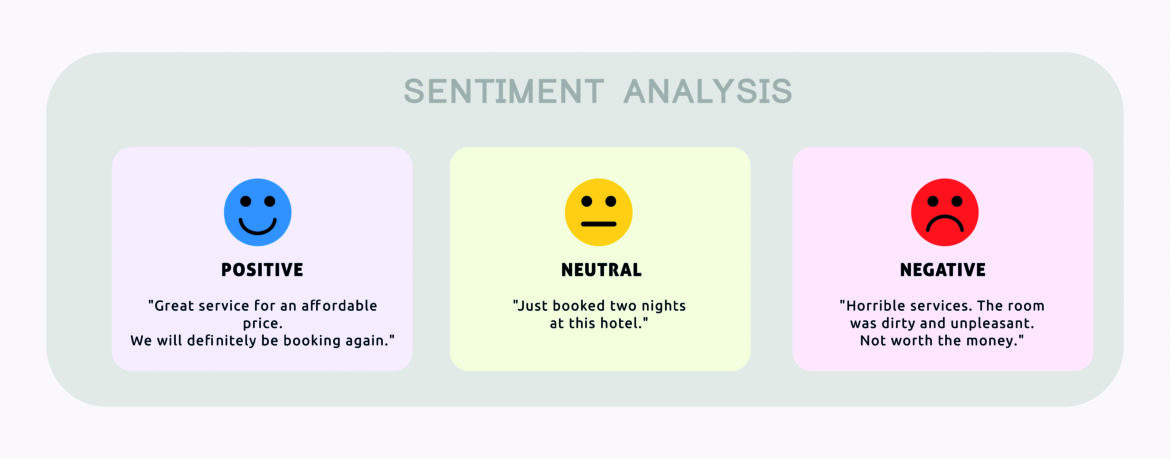

Our brains can process language with minimal effort. Even on paper, we can tell how a writer feels by their choice of words, tone of voice, and even letter case. To computers, however, all terms have the same value, meaning they cannot decipher whether a sentence has positive, negative, or neutral sentiment – at least, not unless researchers like Dawson Camilleri teach them how to.

“The first step in this process is for scientists to explain which words fall in each category to an Artificially Intelligent (AI) computer system,” says Dawson, who previously studied Software Development at MCAST.

This is done through datasets containing lists of terms connected with a quantifier. For example, phrases like ‘thanks’ and ‘great’ have a positive sentiment, while ‘expensive’ and ‘upset’ have a negative one. But while this may seem simple, creating them can be a massive undertaking as each word also needs to be ranked.

“Scientists also have to look at each word and determine whether it tells us anything about sentiment,” Dawson continues. “So, while words like ‘beautiful’ or ‘horrible’ explain how a person feels about something, a pronoun, such as the name of a town, or a noun, doesn’t.”

This process has already been undertaken in many major languages, giving AI systems enormous datasets in English and Italian. Maltese datasets also exist, though we are lagging due to fewer speakers, resources, and scientists to work on them.

“That’s where my project comes in,” Dawson explains. “My idea was to use the datasets already available in other languages to create a larger one in Maltese. This can then be used to determine sentiment.”

To test his theory, Dawson looked at using two separate approaches.

In the first one, Dawson translated a test dataset from Maltese into English before feeding it into an AI system that had been trained on an English dataset. In other words, the system knows ‘bad’ has a negative sentiment and knows that ‘ħażin’ is the Maltese word for ‘bad’, leading it to conclude that ‘ħażin’ carries negative sentiment.

Meanwhile, in the second approach, Dawson translated an English dataset and an Italian dataset into Maltese before teaching the AI system what each word in Maltese inferred.

“The translation of these datasets was done automatically using Google Translate API,” he continues, “but each dataset had to be processed in a way that would guarantee maximum accuracy… Moreover, the AI systems had to be taught to recognise Maltese characters.”

This system is still in the works, but its contribution to creating an accurate and usable dataset of Maltese words in sentiment analysis could be enormous.

“When these datasets are completed, they are then inputted into the sentiment classifier of the AI system so that it can run sentiment analyses. In other words, it can compare the terms in a sentence with those in the positive or negative rankings lists.

“Such software can then be used in many industries”

“Such software can then be used in many industries,” he explains. “In marketing, this could allow companies to monitor related comments on social media and understand how people feel about the brand. In journalism, this could help give feedback on whether articles, which should be objective, have a hidden agenda or political bias. And, for owners of websites or news sites in Maltese, such a system could help eliminate spam in the comments section to ensure its integrity.”

A tool such as this also serves another purpose: to make working in Maltese as accessible and as easy as it is with other languages. This makes the continued use of our language possible, even as our society moves forward, showing that ICT is also about preserving our identity, culture, and language.