Autonomous guided vehicles have long been used in factories and warehouses, but could they soon find their way into care homes? Master’s student MARK MIZZI is certainly working towards it.

Care homes are a practical and emphatic solution to ensuring that elderly people who can no longer take care of themselves find the help they need to go about their day-to-day lives. Even so, it doesn’t change the reality that a number of those who enter care homes may not like the fact that their autotomy is compromised by their age and lack of physical ability. Moreover, while help may be readily given, it often means that the elderly have to wait their turn to be seen to by carers whose tasks and responsibilities are numerous.

Of course, not all of the carers’ tasks can be replaced by technology, nor should they be. The human element in these sorts of situations is incredibly important. Yet technology can offer a much-needed helping hand to carers while giving the patient increased independence, particularly when it comes to mobility.

Of course, not all of the carers’ tasks can be replaced by technology, nor should they be. The human element in these sorts of situations is incredibly important. Yet technology can offer a much-needed helping hand to carers while giving the patient increased independence, particularly when it comes to mobility.

“In many factories and warehouses around the world, materials and products are transported around using AGVs that work without the need of human assistance,” says Mark, who is now continuing his studies through a Master’s in Computer Information Systems.

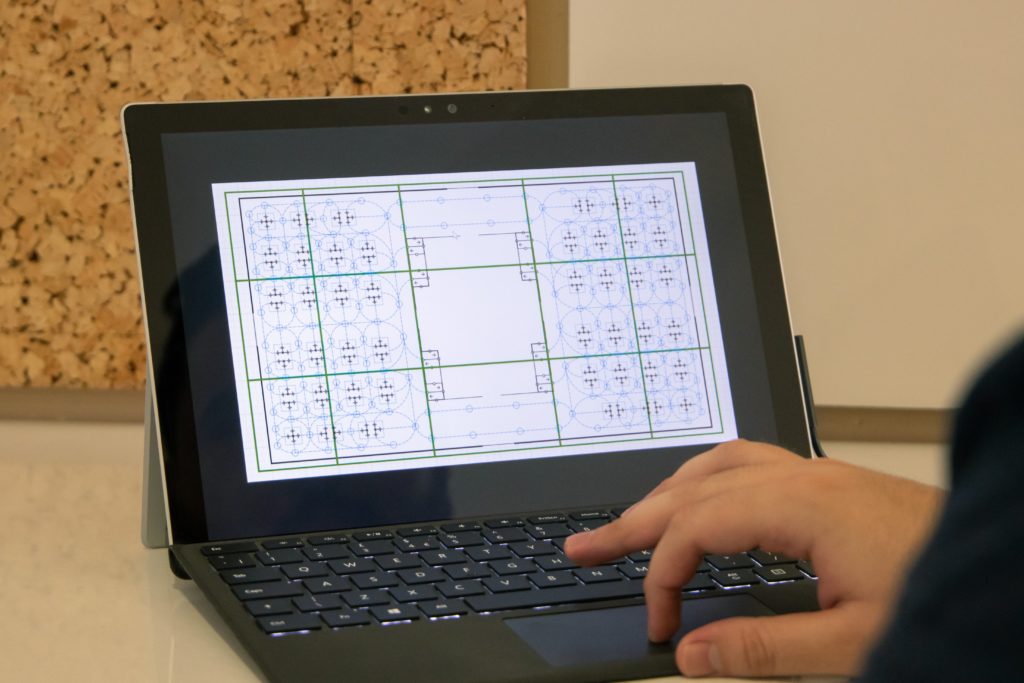

“These AGVs are usually connected to one of three systems. The first is the centralised approach, where a server has a digital map of the floor and can send out instructions to the AGV with what needs to be collected, where it needs to be delivered, and the best route to take to get the objects from Point A to Point B along with which obstacles will need to be avoided. The second is the decentralised approach, where the AGVs communicate among themselves to decide which one of them is closest to the objects needed and to find the best route to deliver it.”

While each of these systems is used by numerous businesses, there are pitfalls. The centralised approach, for example, can have ‘system blackholes,’ which means the system won’t be able to reach certain parts of the premises. The decentralised approach, meanwhile, sees the AGVs solely communicating with other AGVs with no central system overseeing the process, thus resulting in wasted time and a higher number of collisions.

“This is where the third system, the hierarchical approach, comes in,” Mark continues. “This approach removes the majority of the cons of the first two approaches by having a centralised system that sends out the information and maps out the route, and then a decentralised system which sees the AGVs communicating to avoid collision, obstacles, bottlenecks and so on.”

You may be wondering what this has to do with care homes, but given that in some care homes up to 50 per cent of elderly residents need to make use of a wheelchair, utilising such systems could have a huge impact on both carers and residents

“Smart wheelchairs have long been researched and used in care homes, but when it comes to navigating a space, these wheelchairs fall short of what they promise,” Mark continues. “One of their major shortcomings is that they cannot predict the best route based on traffic, meaning that having a number of them in one care home could see the corridors and halls turn into absolute mayhem that can only be solved by human beings.

“Therefore, one of the main advantages of using the hierarchical approach in care homes would be that residents who need to move from one place to another using a wheelchair would be able to do so by themselves. All without the worry of getting stuck in internal traffic jams or coming across obstacles that the smart wheelchairs can’t predict.”

These traffic jams are not something that may occur only in the future, either. Through his research, for which he interviewed a number of managers of local care homes, Mark has discovered that even traditional wheelchairs tend to end up in bottlenecks, often causing loss of time for the carers and an inconvenience to the residents.

Such a system, therefore, would see the residents travel more freely inside the care home, see one of the carers’ most time-consuming tasks being removed from their to-do list, and make managing the care home that much easier thanks to the server that oversees the process of residents moving about.

At the time of writing, the hierarchical system Mark is suggesting for care homes is being tested using simulation, but he expects it to be ready for real-life testing in the years to come – and, who knows, it may just give the elderly residents of Malta and Gozo’s care homes more independence than is currently possible for them to have.